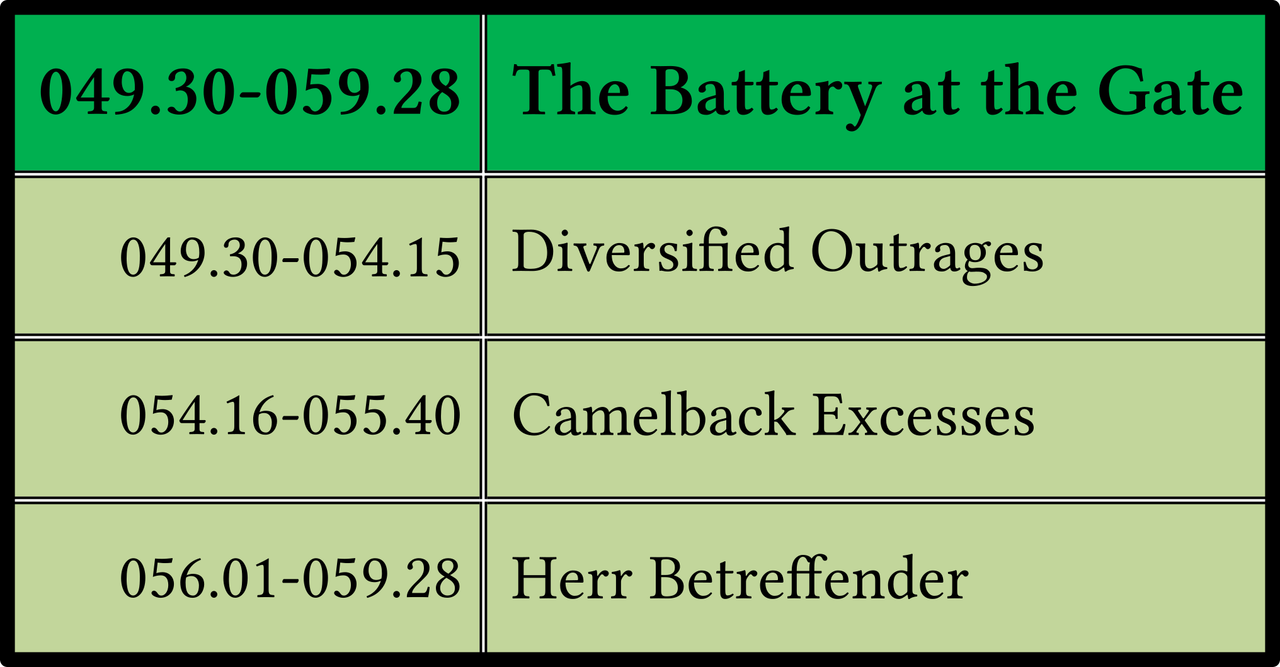

Earwicker, that Patternmind (RFW 056.38–058.09)

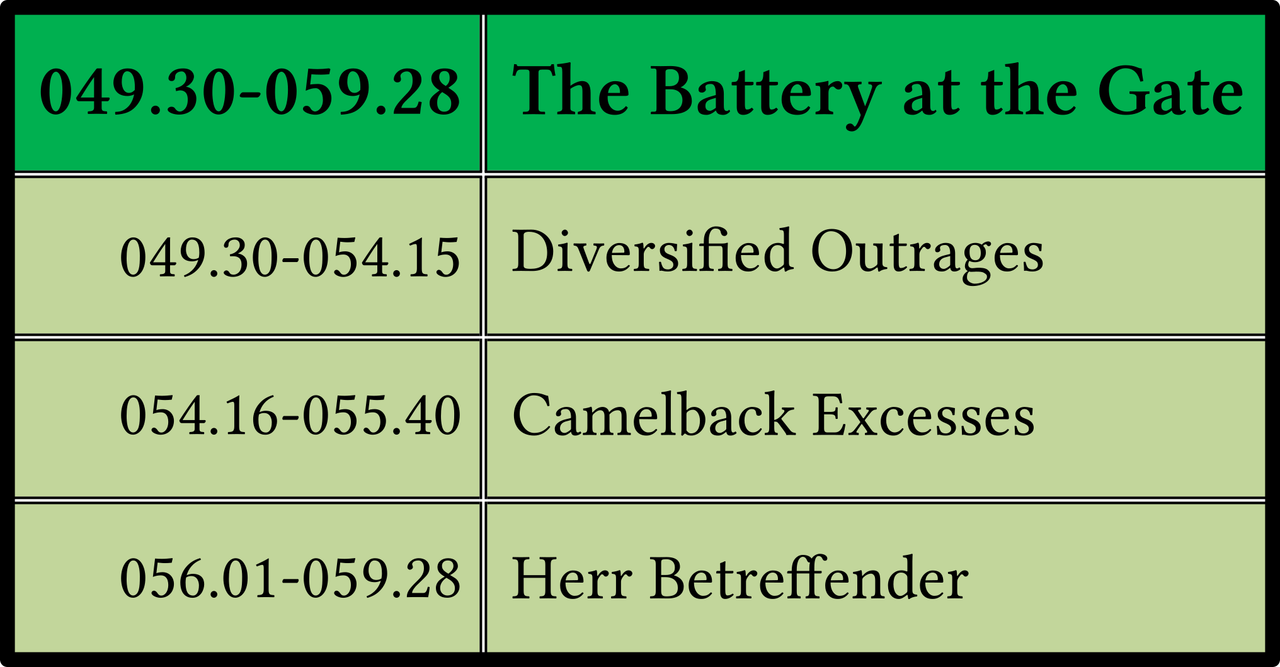

The last ten pages of Chapter 3 of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake comprise an episode known as The Battery at the Gate. In the previous two paragraphs HCE suffered a verbal assault at the hands of a travelling salesman, who began life as an Austrian called Herr Betreffender before morphing into an American. In this paragraph HCE compiles a list of all the abusive names he was called during the Battery.

First Draft

The first-draft version of this paragraph consisted of a single sentence:

Earwicker, longsuffering, compiled a long list of all the abusive names he was called but did not other wise reply because, as he afterwards explained, the dominican mission was on at the time & he thought that might reform him. ―Hayman 74

The main difference between this early draft and the final published version is the inclusion of HCE’s long list―part of it, at any rate―of abusive names. Other than that, Joyce added little that is new, though he did elaborate everything in the first draft after his usual practice.

Danis Rose & John O’Hanlon have also restored a paragraph break after Gonn, which is not in the first edition. In the original edition this paragraph begins and ends in the middle of a long paragraph, so Rose & O’Hanlon have actually restored two paragraph breaks.

St Dominic de Guzmán

The Dominican Mission

What is the significance of the Dominican mission? Does HCE hope that the Dominicans will reform Herr Betreffender? The final version refers to the Romish devotion known as the Holy Rosary. St Dominic de Guzmán, the founder of the Dominican Order or Order of Preachers, is said to have introduced the Holy Rosary to the Catholic Church after being miraculously visited by the Virgin Mary in 1214. HCE is a Protestant―he is even called a fundamentalist―which is why he refers to the Rosary as Romish. Like papish or popish, this term is generally used by Protestants to refer to the Catholic Church in a derogatory sense.

Blackfriars was mentioned on the opening page of this chapter. In England the Dominicans are popularly known as the Black Friars.

Giordano Bruno―with Giambattista Vico and Dante Alighieri, one of the three Patron Saints of Finnegans Wake―was a Dominican friar. He later abandoned the order and embraced Calvinism. The Roman Inquisition, which subsequently condemned him of heresy and had him burnt at the stake in Rome, was recruited from the Dominican Order. (The Spanish Inquisition, which was also Dominican, is mentioned in the quotation taken from Edward Creasy below.)

Missionary work plays a prominent role in the affairs of the Order. St Dominic himself led a mission to convert the Manichaean Albigenses or Cathars of Languedoc. He took no part in the subsequent Crusade against them, though he supported the campaign. The Dominican Mission HCE refers to is being held for the Socialist Party. This is a curious combination, as socialism is often associated with atheism. Six lines above, there is even an allusion to anarchism, which is also often associated with atheism.

The Duke of Marlborough Signing the Despatch at Blenheim

Joyce’s source for the word Romish was Edward Creasy’s The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World (1915). Referring to the Battle of Blenheim, in which John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, led the Grand Alliance to victory over Louis XIV’s French and Bavarian forces. Creasy quotes from Archibald Alison’s biography of Churchill, The Military Life of John, Duke of Marlborough (1848):

‛The Protestants might have been driven, like the Pagan heathens of old by the son of Pepin, beyond the Elbe; the Stuart race, and with them Romish ascendancy, might have been reestablished in England; the fire lighted by Latimer and Ridley might have been extinguished in blood; and the energy breathed by religious freedom into the Anglo-Saxon race might have expired. The destinies of the world would have been changed. Europe, instead of a variety of independent states, whose mutual hostility kept alive courage, while their national rivalry stimulated talent, would have sunk into the slumber attendant on universal dominion. The colonial empire of England would have withered away and perished, as that of Spain has done in the grasp of the Inquisition. The Anglo-Saxon race would have been arrested in its mission to overspread the earth and subdue it. The centralized despotism of the Roman empire would have been renewed on continental Europe; the chains of Romish tyranny, and with them the general infidelity of France before the Revolution, would have extinguished or perverted thought in the British islands.’ ―Creasy 304 : Alison 367

The spellings rowmish and rowsary are probably due to the row between HCE and Herr Betreffender.

The List

The initial draft of this passage did not include HCE’s list of abusive names, and when the list made its first parenthetical appearance in the second draft, it had only a few items:

(informer, old fruit, yellow whigger, wheatears, goldygoat, bogside beauty, muddle the plan, mister fatmeat) ―James Joyce Digital Archive

Joyce’s drafts are notoriously difficult to decipher, which may explain why David Hayman’s initial draft of the list differs from that of Rose & O’Hanlon on the JJDA:

(informer, old fruit, funnyface, yellow whig, Bogsides, muddle, plander) ―Hayman 74

Or perhaps these are two different drafts. Whatever the truth, both are dwarfed by the final list, which has over one hundred items. In their Chicken Guide to Finnegans Wake Rose & O’Hanlon count 111 items:

A list of one hundred and eleven abusive names is cited on pages [RFW] 57–8. ―JJDA, Chicken Guide Note 84

William Tindall also counted 111 (Tindall 78). There are a few reasons why 111 is a significant number in Finnegans Wake:

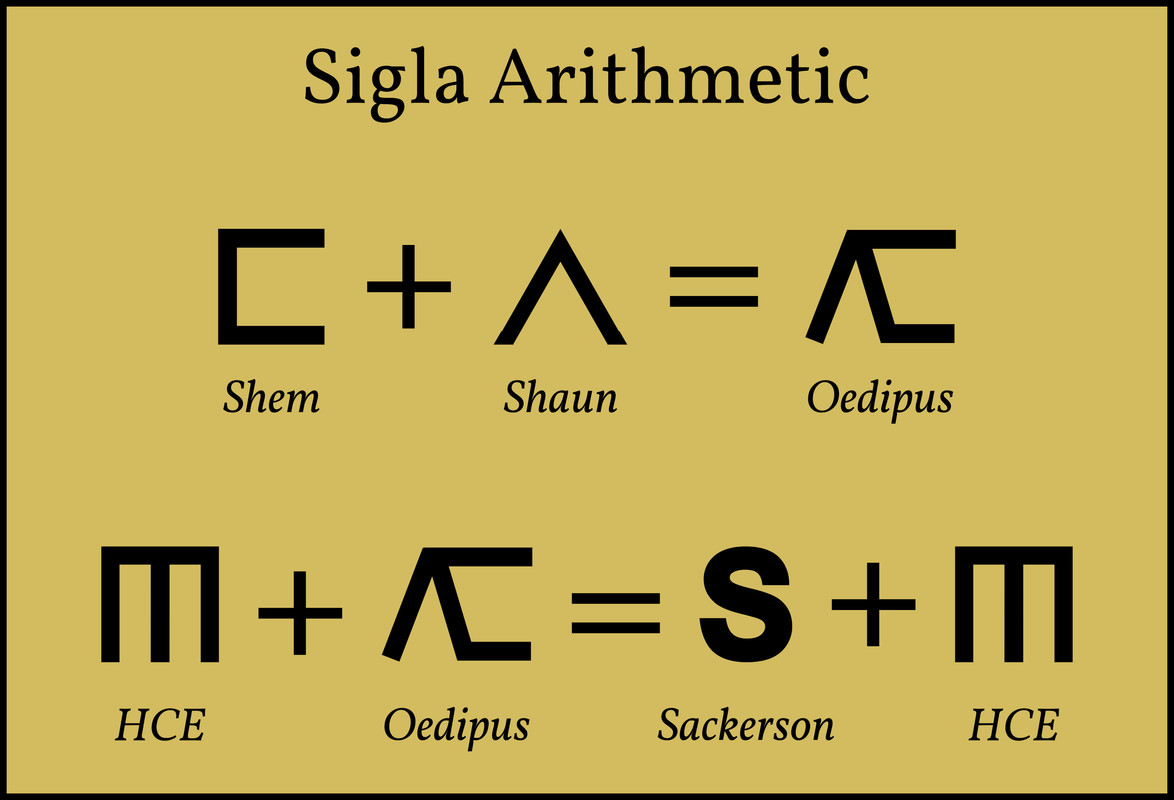

HCE and ALP have three children. In Roman numerals three is III, which resembles 111.

In Greek numerals: A (alpha) = 1 : Λ (lambda) = 30 : Π (pi) = 80. Therefore ALP = 111.

transition (Jolas & Paul 48)

When an early draft of this chapter appeared in transition in 1927, there were only fifty-odd items in the list. Are there actually 111 names in the final list? The items are separated by commas, but some commas appear to be internal (ie intrinsic members of an item), so counting is not a trivial task. I count 114 items. Other Joyceans have come up with different numbers. Alfred G Engstrom, for example, counted 120 (Daniel 66). Joseph Campbell & Henry Morton Robinson counted 113 in their Skeleton Key (Campbell & Robinson 77).

Two items in the list are blank. One of these is represented by two em dashes, as though a two-word abusive title has been suppressed. The other is represented by a single em dash. There is also a three-word title with the first word He followed by two em dashes. If these three are omitted, the tally comes to 111.

To confuse matters, there are discrepancies between transition, the first edition of 1939 and Rose & O’Hanlon’s restored edition of 2010. In the 1939 edition the first of the two blanks items consists of a single em dash, and this is followed by an apostrophe, not a comma (but this is probably a typo). The second blank item is missing altogether.

Finally, there is Joyce’s poor eyesight to take into account. It is quite possible that he wanted there to be precisely 111 items in the list, even if in fact there aren’t.

The Museyroom Again

The Battery at the Gate is another retelling of the Wake’s Oedipal Event, in which HCE is confronted by a younger adversary. The Museyroom episode in the opening chapter was the first extended version of this important engagement. It is by design, then, that the present paragraph contains a few echoes that hark back to the Museyroom:

- lacies in loo water, flee, celestials, one clean turv Not only do we have here an allusion to Waterloo, which was reenacted in the Museyroom episode, but also an echo of the Museyroom’s: Penetrators are permitted into the museomound free. Welsh and the Paddy Patkinses, one shelenk. Celestials is a slang term for the occupants of the gallery in a theatre or opera house. Another reenactment of Waterloo took place in the Gaiety Theatre on South King Street, where HCE attended a performance of W G Wills’ A Royal Divorce (RFW 026.01 ff).

The Battle of Inkerman

The Museyroom episode foreshadows the Wake’s most sustained reenactment of the Oedipal Event: How Buckley Shot the Russian General, which is set during the Crimean War and involves the strategic use of one clean turv. So here we also have an allusion to that military engagement:

the collision known as Contrastations with Inkermann The Battle of Inkerman was fought in the fog near Sevastopol on 5 November 1854. It was mentioned on the opening page of this chapter. There is also an obvious allusion here to Johann Peter Eckermann’s Conversations with Goethe, though the relevance of this work escapes me.

clean turv also alludes to Clontarf, the scene of another famous battle that figures prominently in Finnegans Wake. In the Buckley anecdote the Russian General cleans his arse with a sod of turf―the final insult to the Ould Sod, which causes Buckley to shoot him.

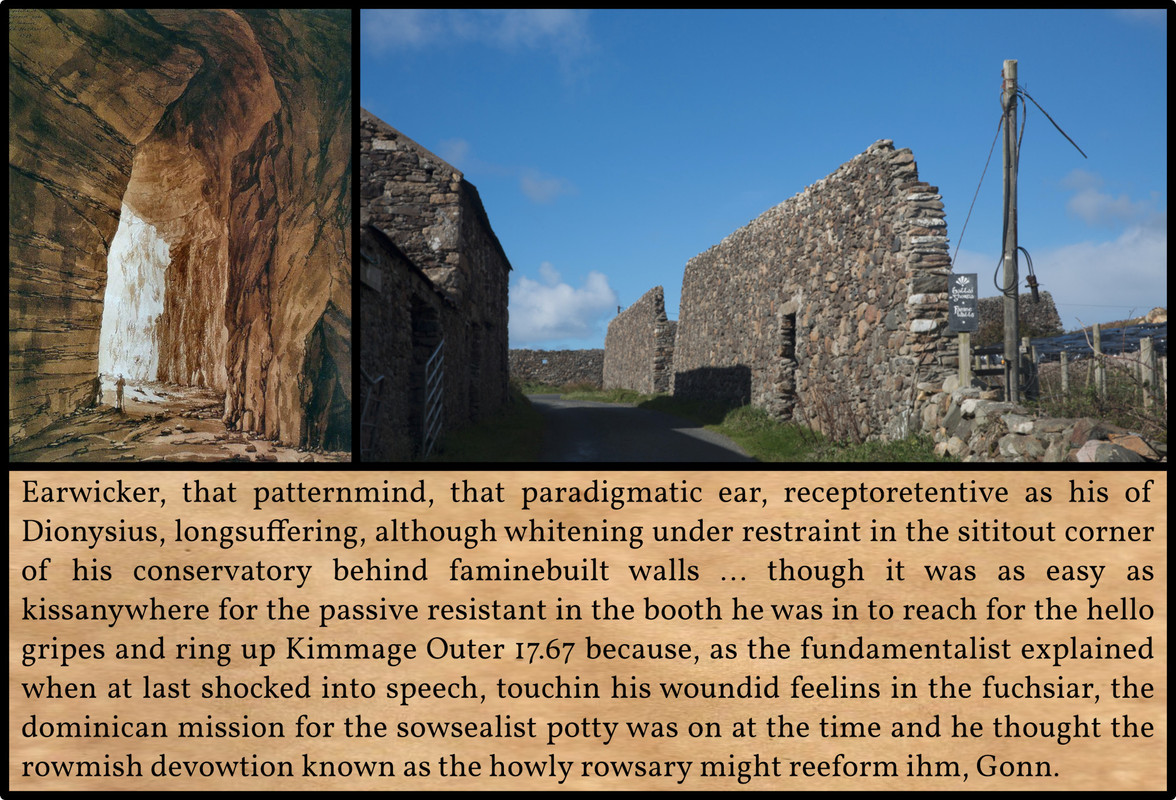

Telephone Booth

In the previous chapter an account of HCE’s Oedipal Encounter in the Park with the Cad underwent a series of transformations as it was passed from gossip to gossip. This process has been compared to the children’s game of Chinese Whispers, or Telephone. In this chapter HCE’s refuge from his attacker also undergoes a bewildering series of metamorphoses:

the southeast bluffs of the stranger stepshore, a regifugium persecutorum ―RFW 041.40 f

The seventh city, Urovivla, his citadear of refuge, whither … the hejirite had fled ―RFW 049.37 ff

The coffin, a triumph of the illusionist’s art … had been removed from the hardware premises of Oetzmann and Nephew ―RFW 053.24 ff

A stonehinged gate there was for another thing while the suroptimist had bought and enlarged that shack … he put an applegate on the place … and just thenabouts the iron gape … was triplepatlockt on him on purpose by his faithful poorters to keep him inside probably ―RFW 055.28 ff

Humphrey’s unsolicited ad hock visitor … after having blew some quaker’s (for you, Oates!) in through the houseking’s keyhole ―RFW 056.19 ff. The King’s House was a stately edifice in Chapelizod, in which King William III stayed after the Battle of the Boyne.

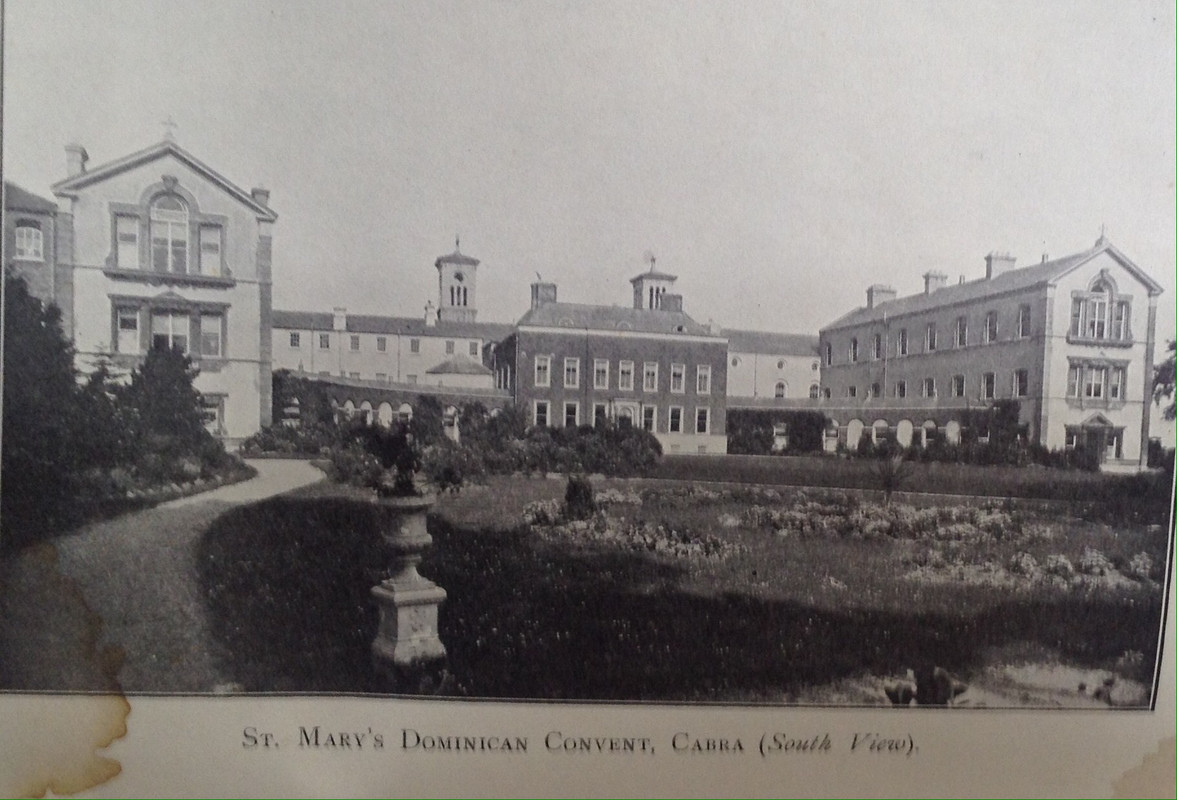

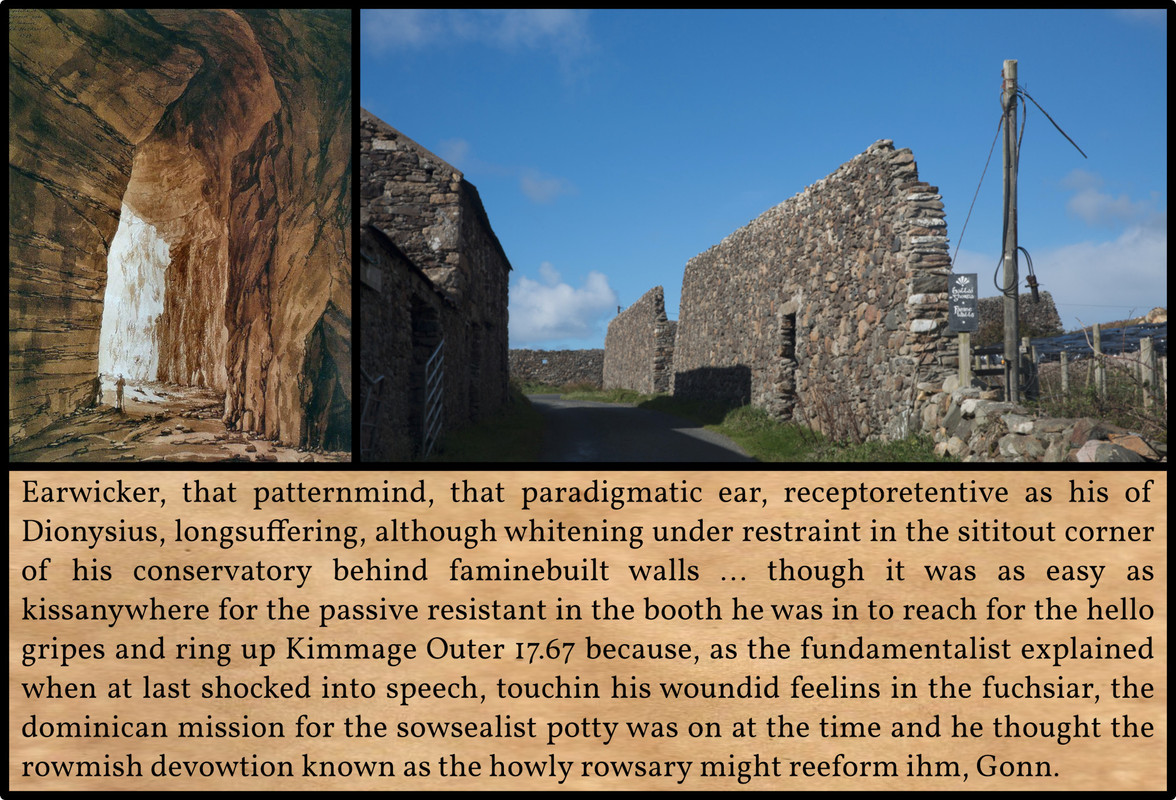

Earwicker … longsuffering, although whitening under restraint in the sititout corner of his conservatory behind faminebuilt walls ―RFW 056.38 ff

it was as easy … in the booth he was in to reach for the hello gripes and ring up Kimmage Outer 17.67 ―RFW 058.03 ff

in the siegings round our archicitadel ―RFW 059.02

his chambered cairns ―RFW 059.06

1920’s Telephone Booth on Dawson Street

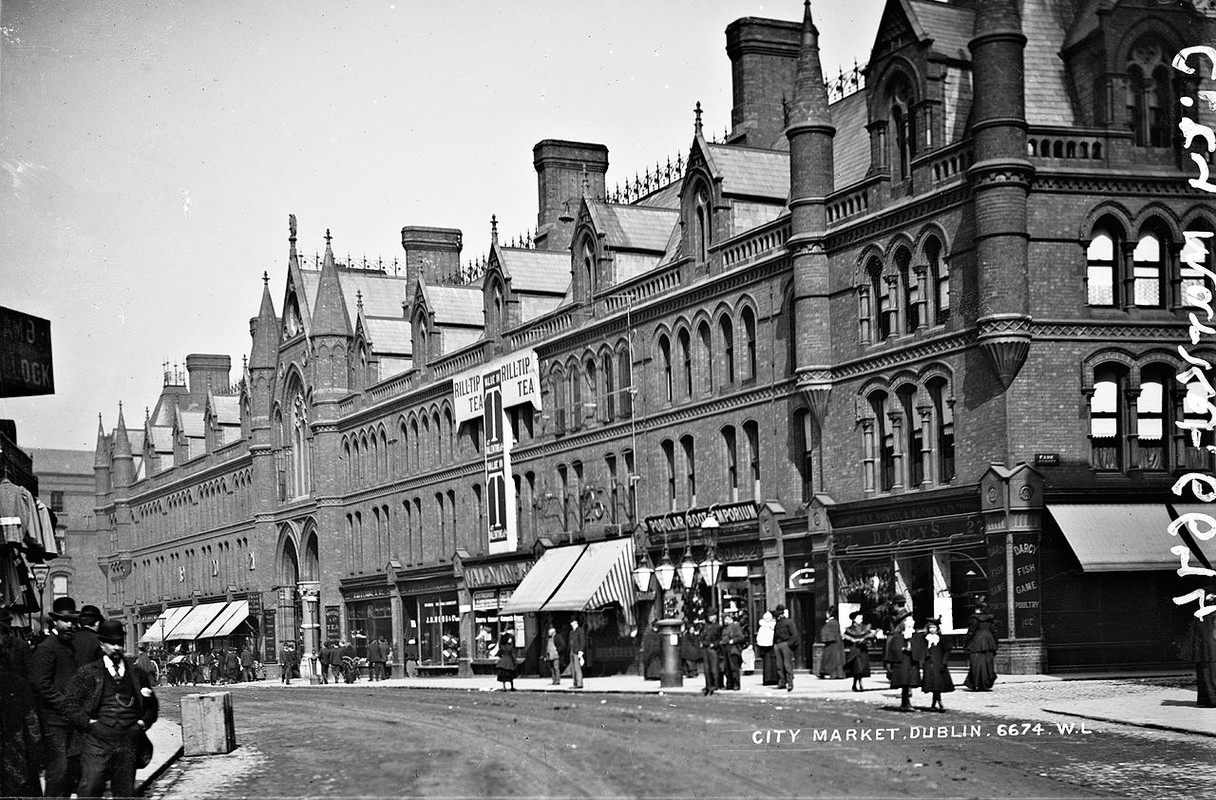

In this paragraph HCE’s refuge begins as the corner of a conservatory behind famine walls―useless walls built as work-relief schemes during the Great Famine, because the Victorians thought that even starving people should work for their food. By the end of the paragraph, however, HCE seems to be in a telephone booth. It is as though Herr Betreffender is insulting him over the line. And when HCE is shocked into speech we are presumably talking about an electric shock from the telephone.

Kimmage Outer 17.67 is generally glossed as the local telephone exchange followed by the phone number. Sherdan Le Fanu’s novel The House by the Churchyard begins with A.D. 1767. Like Finnegans Wake, The House by the Churchyard is set in Chapelizod, and is a key work for the proper understanding of Joyce’s novel. One of Joyce’s notes reads:

He called up Crumlin Exchange ―VI.B.11:144a

An early draft of this passage has call up Crumlin exchange (Hayman 74). Kimmage and Crumlin are neighbouring suburbs of Dublin. It is possible that this Crumlin Exchange refers to another Crumlin in County Antrim. I have no idea what Joyce’s source for this note was or what the significance is of either Kimmage or Crumlin.

Coffin Bell and Safety Coffin

In an earlier article―Chest Cee!―I suggested that the zimzim motif, which is usually associated with the Magazine Wall in the Phoenix Park, might be a reference to a safety coffin. This was a coffin fitted with some sort of bell or telephone to allow the occupant to communicate with the living in case they have been buried alive and have subsequently risen from the dead. Note that HCE’s list of abusive names includes one that seems to allude to vampires (immediately after one that calls him a Lycanthrope, or werewolf):

Flunkey Beadle Vamps the Tune Letting on He’s Loney ―RFW 057.25

Loose Ends

It would take too long to go through all the abusive names in HCE’s list, so I will conclude with just a few outstanding items:

- that paradigmatic ear, receptoretentive as his of Dionysius The Ear of Dionysius was an artificial limestone cave near Syracuse, Sicily. The cave was given its name in 1608 by the painter Caravaggio. Dionysius I was a Greek tyrant who ruled Syracuse in the early 4th century BCE. According to legend, he had the cave constructed as a prison for political dissidents. The cave’s perfect acoustics allowed him to eavesdrop on his captives through an opening at the top. This legend is now widely discredited.

The Ear of Dionysius

the rejoicement of foinne ladies ind the humours of Milltown In this paragraph Joyce continues to mine Charles Villiers Stanford’s Complete Collection of Irish Music as Noted by George Petrie. FWEET lists a further eighteen traditional tunes to add to the twelve we have already had. Of these, all but the first two―The Rejoicement of the Fian Ladies and The Humours of Milltown―occur in HCE’s list of abusive titles. Milltown is a town in County Clare, but there is also an allusion to John Milton, whose Paradise Lost is hidden in the parenthesis above: now feared in part lost. In passing, I might mention that Joyce also dropped three final items from Downing’s Digger Dialects into this paragraph. There will be more of these before we reach the end of Finnegans Wake, but the next does not appear until I.6.11 (Question 11 in The Quiz).

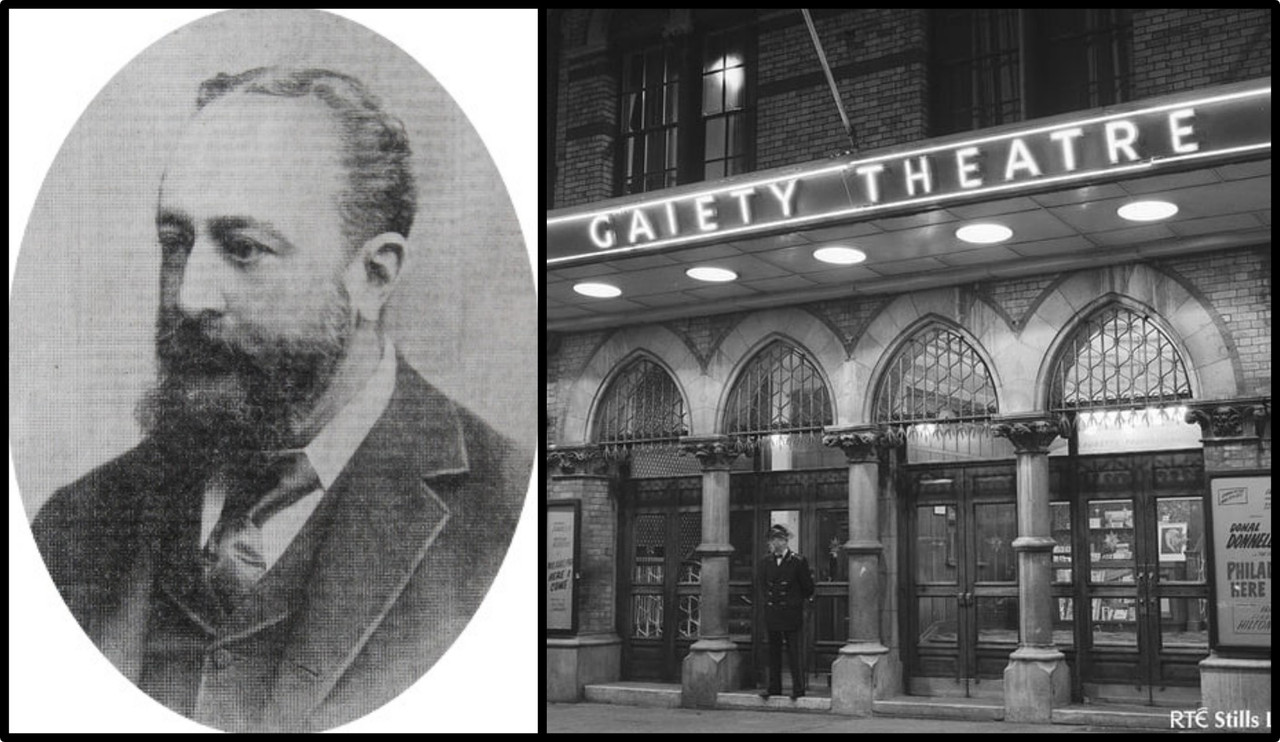

Gonn In transition this was spelt Gunn. The manager of Dublin’s Gaiety Theatre Michael Gunn, puts in several appearances in Finnegans Wake:

Gunn, as producer of the pantomime that is human history, is a role of HCE’s. ―Glasheen 112

Michael Gunn & The Gaiety Theatre

And that’s as good a place as any to beach the bark of our tale.

References

- Archibald Alison, The Military Life of John, Duke of Marlborough, Harper & Brothers, New York (1848)

- Joseph Campbell, Henry Morton Robinson, A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake, Harcourt, Brace and Company, New York (1944)

- Edward Creasy, The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World: From Marathon to Waterloo, Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, London (1915)

- Alfred G Engstrom, A Few Comparisons and Contrasts in The Wordcraft of Rabelais and James Joyce, George Bernard Daniel (editor), Renaissance and Other Studies in Honor of William Leon Wiley, The University of North Carolina Press (2017)

- Adaline Glasheen, Third Census of Finnegans Wake, University of California Press, Berkeley, California (1977)

- David Hayman, A First-Draft Version of Finnegans Wake, University of Texas Press, Austin, Texas (1963)

- James Joyce, Finnegans Wake, The Viking Press, New York (1958, 1966)

- James Joyce, James Joyce: The Complete Works, Pynch (editor), Online (2013)

- Danis Rose, John O’Hanlon, The Restored Finnegans Wake, Penguin Classics, London (2012)

- William York Tindall, A Reader’s Guide to Finnegans Wake, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York (1969)

Image Credits

- The Ear of Dionysius: Jacob Philipp Hackert (artist), Galeries nationales du Grand Palais, Paris, public Domain

- Famine Wall (Maghery, County Donegal): © Singersong (photographer), Fair Use

- St Dominic: Pieter Thijs (artist), Maagdenhuismuseum, Antwerp, Public Domain

- The Duke of Marlborough Signing the Despatch at Blenheim: Robert Alexander Hillingford (artist), Private Collection, Public Domain

- transition: Eugene Jolas & Elliot Paul (editors), transition, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public Domain

- The Battle of Inkerman: Adolphe Bayot (artist), François Delarue (engraver), E Gambert & Co, London (1855), Public Domain

- 1920’s Telephone Booth on Dawson Street: © Sam McGrath (photographer), Fair Use

- Coffin Bell: Halloween Prop, The Haunted Borough, Marlborough, MA, © Dave & Nancy Adams, Fair Use

- Safety Coffin: Life-Preserving Coffin in Doubtful Cases of Actual Death, Christian Henry Eisenbrandt (designer), Baltimore, MD, Public Domain

- The Ear of Dionysius: © Collector of Experiences (photographer), Creative Commons License

- Michael Gunn: Anonymous Photograph, Public Domain

- The Gaiety Theatre: Phil Dowling (photographer), © RTE, RTE Stills Library, Fair Use

Useful Resources